Chord Construction

How To Build Guitar Chords

In this comprehensive lesson on chord building, we will uncover the theory behind the chord shapes we are familiar with.

In this comprehensive lesson on chord building, we will uncover the theory behind the chord shapes we are familiar with.

From there, we’ll learn how to create new chord shapes across the fretboard, combining music theory with the geometry of the fretboard.

Why Should I Learn Guitar Chord Theory?

Typically, guitarists focus on memorizing as many chord fingerings as possible, treating them as static shapes.

There are tons of chord patterns: open strings, barre shapes, higher positions, and more.

The most common approach to learning chords is to use a chord dictionary and brute force memorize all those diagrams until muscle memory allows us to play them without much thought.

This practice is a good foundation, but it’s just the starting point. From there, you should expand your chord knowledge and truly learn how chords are constructed.

If you view a chord as a static shape on the fretboard, you will severely limit your options for expanding your sound and fully expressing yourself on the guitar.

What if you could modify a chord by adding or substituting notes within its shape with intention?

Or even create chords on the fly anywhere on the fretboard, depending on the musical feeling you want to evoke at any given moment?

To master these skills, you first need to understand chord theory and how to apply it to the guitar. This guide will help you with that.

What You'll Learn In This Tutorial

- What chords really are

- What intervals are and how to stack them to create harmony

- Why well-known chords like C major or E minor have their familiar shapes

- How different interval combinations create different types of chords

- How to construct chords on the fly across the entire fretboard

Introduction: Melody vs. Harmony

The three main pillars of music theory are melody, harmony, and rhythm.

Melody is created by playing single notes one after another, like when playing a scale.

Conversely, harmony involves the rules that dictate what happens when one or more instruments play multiple notes simultaneously.

A vast palette of different feelings and colors lies behind harmony.

In this guide, we will focus on harmony, which is directly related to chords.

The Basics: What Creates A Chord

Classical music theory defines a chord as a sound composed of three or more notes played simultaneously.

Some options to play a C major chord

On the guitar, we can simplify this definition and say that a chord is created when you play frets on different strings at the same time, producing multiple notes together.

This is the opposite of playing a scale, where you play one fret at a time. Depending on the chord shape, you can use three or more strings.

For example, with a G major chord in the first position, you play all six strings, while for a D minor chord, you only play four strings.

We’ll explore the reasons for this as we continue through this tutorial.

A chord is usually identified by its root and its type (or quality).

Chord Root: The "C" in "C Major"

The root of the chord is simply the note that gives the chord its name.

The root is the most important tone of the chord, serving as the foundation (or home base) for the other tones that compose the chord.

Often, this note is the lowest string in a chord fingering.

When this happens, the chord is said to be in root position.

If the root is not the lowest note, we have a chord inversion; we’ll discuss this concept later.

For now, just know that a chord in root position has the root note at the bottom, which gives the chord its name.

Some examples:

- In the C major chord, the root note is C, which is also the lowest note of the chord.

- In the A minor chord, the root and lowest note is A.

- In the E7#9add13 chord, the root note is E. The more complex part is the chord type (a dominant with a sharp ninth and an added thirteenth, but don’t worry if this sounds confusing now).

Chord Type: The "Major" in "C Major"

The type, or quality, of a chord is determined by the distance between the root and the other notes, and how these distances combine.

Depending on these distances, we can have various chord types: major, minor, dominant, seventh, diminished, suspended, and many others.

These distances in music are called intervals...

Intervals: The Building Blocks of Chords

To master chord theory, the most important concept to understand is the interval.

An interval is simply the distance between two pitches.

On the fretboard, this concept is easily visualized, as intervals can be expressed as the distance between two frets.

Before moving on, be aware of some oddities in the world of intervals:

- The same distance between two pitches can have different interval names.

- Two intervals with different names can sound the same.

These seemingly strange behaviors stem from the development of Western music theory over centuries.

Different names or sounds for the same thing can be confusing, but with proper guidance, understanding intervals will be easy, and you’ll avoid confusion.

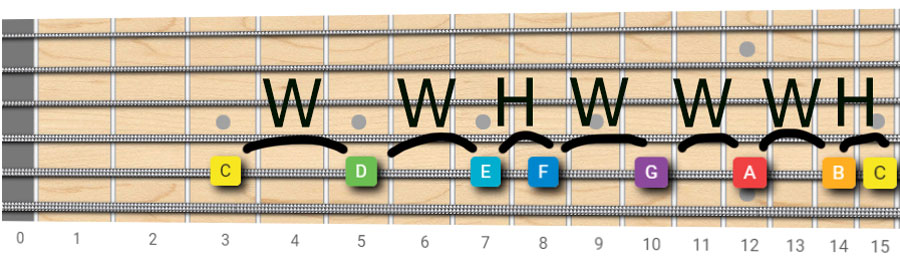

Let’s start with the major scale:

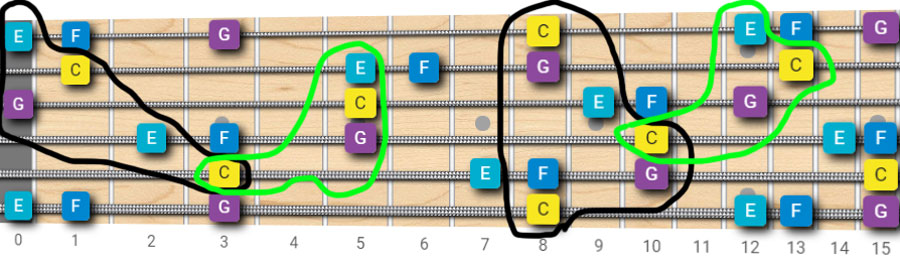

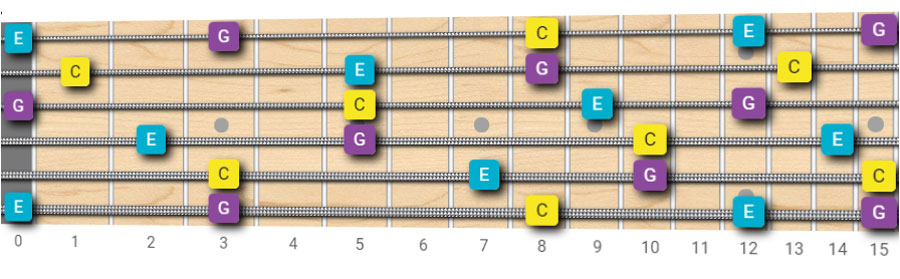

Here are the notes of the major scale laid out horizontally on the fretboard:

Here’s some terminology you’ll need:

The "unit of measurement" for intervals is the whole-step.

Guitarists should know that a whole-step is equivalent to two frets on the instrument.

A half-step? That’s just one fret. So, to recap:

- 2 frets = 1 whole-step (often denoted as W), also called a tone.

- 1 fret = 1 half-step (often denoted as H), also called a semitone.

Looking at the picture above, we can make some observations:

- The distance between each note and the next is two frets (1 whole-step), except for the pairs E-F and B-C, which are just one fret apart (1 half-step).

- From C to D there is 1 whole-step (2 frets), called a Major Second.

- From C to E there are 2 whole-steps (4 frets), called a Major Third.

- From C to F there are 2 whole-steps + 1 half-step (5 frets), called a Perfect Fourth.

- From C to G there are 2 whole-steps + 1 half-step + 1 whole-step (7 frets), called a Perfect Fifth.

- From C to A there are 2 whole-steps + 1 half-step + 2 whole-steps (9 frets), called a Major Sixth.

- From C to B there are 2 whole-steps + 1 half-step + 3 whole-steps (11 frets), called a Major Seventh.

- From C to the upper C there are 2 whole-steps + 1 half-step + 3 whole-steps + 1 half-step (12 frets), called an Octave.

So What Does WWHWWH Mean? (You Should Know the Answer Now)

You’ve likely encountered this notation before.

Now, you should know that this set of symbols describes the major scale.

Indeed, WWHWWWH means 2 whole-steps, 1 half-step, 3 whole-steps, and 1 half-step.

C-W-D-W-E-H-F-W-G-W-A-W-B-H

(Look at the fretboard picture above and you’ll notice that E-F and B-C are only one fret apart, or 1 half-step, also called a semitone.)

Interval Types

The table below shows the seven main interval types in the major scale:

| Note | Interval | Semitones |

|---|---|---|

| C | Root | 0 |

| D | Major Second | 2 |

| E | Major Third | 4 |

| F | Perfect Fourth | 5 |

| G | Perfect Fifth | 7 |

| A | Major Sixth | 9 |

| B | Major Seventh | 11 |

| C | Octave | 12 |

Now, here’s the tricky part: we can raise or lower an interval and get a different type of interval.

By "raising" or "lowering," we mean increasing or decreasing the distance between the two notes that make up an interval.

We can change that distance by 1 half-step up or down (1 fret on the fretboard), or even by 1 whole-step (2 frets on the fretboard).

The table below shows what happens if you lower (by 1 half-step) or raise (by 1 half-step) one of the main intervals of the major scale:

| Flat Interval (1 hs down) | Interval | Sharp Interval (1 hs up) |

|---|---|---|

| Minor Second (1 hs) | Major Second (2 hs) | Augmented Second (3 hs) |

| Minor Third (3 hs) | Major Third (4 hs) | Augmented Third (5 hs) |

| Diminished Fourth (4 hs) | Perfect Fourth (5 hs) | Augmented Fourth (6 hs) |

| Diminished Fifth (6 hs) | Perfect Fifth (7 hs) | Augmented Fifth (8 hs) |

| Minor Sixth (8 hs) | Major Sixth (9 hs) | Augmented Sixth (10 hs) |

| Minor Seventh (10 hs) | Major Seventh (11 hs) | Augmented Seventh (12 hs) |

| Octave (12 hs) |

See the potential for confusion? We have some intervals that have different names but the same distance (and thus the same sound).

Also, why is an interval lowered by 1 step sometimes called "minor" (e.g., minor second) and other times "diminished" (e.g., diminished fifth)?

Welcome to the strange world of enharmonics.

Enharmonic Equivalents

"In modern musical notation and tuning, an enharmonic equivalent is a note, interval, or key signature that is equivalent to another note, interval, or key signature but "spelled" or named differently."

Okay, but why do intervals have different names?

The answer is context!

The same note or interval can have a different function depending on the musical context in which it is used.

For example, you can play the 4th fret of the lowest E string and call it G# or Ab depending on the musical key you're in.

Drill down: We have a separate tutorial on enharmonics to help you fully grasp this counterintuitive topic.

Connecting Fretboard Distances to Sound

So far, we’ve considered intervals as geometric concepts.

But we’re musicians, and we deal with sound! It’s crucial to familiarize yourself with the sound of these intervals.

Take a moment to play some major seconds, major thirds, and perfect fifths on your guitar.

On a single string, select a fret, play it, then move up horizontally by 2, 4, and 7 frets, and play the second note on the same string.

Try to focus on the sound of the interval and sing what you are playing (singing helps a lot in developing your inner ear, as Steve Vai suggests).

Pay attention to the differences in the interval sounds.

One powerful way to memorize and internalize interval sounds is to associate them with the first notes of a song you already know.

Here are some examples taken from very famous tunes, but you should choose songs that you really like.

Memory is all about emotion! (Here’s a post on memory and practice strategies.)

- Major third: first two notes of "When the Saints Go Marching In"

- Perfect fifth: beginning notes of "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star"

There are countless options. For example, are you an Iron Maiden fan like me? Well, here are some memory hooks courtesy of The Irons:

- Major third: first notes of the intro riff of "The Number of The Beast"

- Perfect fifth: first two notes of the riff in the polka-style section of "Mother Russia" (starting at minute 0:54).

Experiment with different intervals and find melodies that contain them.

Okay, I hope you’ve followed along so far. Now we’re going to learn how to combine intervals to create new chords.

To construct a chord, we start from the root of that chord and add two or more notes.

Basic Chords: Major and Minor

Major Chords

By definition, a major chord is constructed with the root, a major third from the root, and a perfect fifth.

Let’s try to build a C major.

Looking at the fretboard image above with the major scale shown horizontally, we see that the note a major third (2 whole-steps, or 4 frets) from the root C is the note E.

Using the same logic, we find that a perfect fifth from the root is the note G (7 frets, or 2 whole-steps, 1 half-step, and 1 whole-step).

So our C major chord is composed of the notes C, E, and G. Keep this information handy.

Minor Chords

By definition, a minor chord is constructed with the root, a minor third, and a perfect fifth.

Referring to the intervals table above, we know that a minor third is a major third lowered by 1 half-step.

So E becomes Eb (E flat).

Drill down: In my complete ebook, Chords Domination | Play Any Chord You Want Across the Fretboard, you’ll find the chord formulas and diagrams for more than 40 types of chords.

A Note on Sharps and Flats

In music notation, we have two symbols that can raise or lower the pitch of a note.

- The sharp (#) raises a note by 1 half-step, or one fret up on the fretboard.

- C# means C raised by one fret, so instead of playing C on the 8th fret of the lowest E string, we play it on the 9th fret.

- The flat (b) lowers a note by 1 half-step (1 fret down on the fretboard).

- Cb means C lowered by one fret, so we play it on the 7th fret of the lowest E string.

Wait a minute! I thought the 7th fret of the lowest E string was a B!

That’s correct, it is B, but also Cb. As explained earlier in the Enharmonic Equivalents section, the name of a note depends on its musical context.

This is a perfect example: our context was the C note, which we flattened by one half-step, thus obtaining Cb (which has the same pitch as B but is named Cb in this context).

Let’s Apply What We’ve Learned So Far to the Fretboard

When it comes to music theory, understanding how the notes are placed on the fretboard is crucial, and this tutorial will help you master the secrets of the fretboard.

Now let’s figure out how to play the C major chord on the guitar.

As we already know, to play a C major chord, we need to play at least three notes simultaneously: C, E, and G.

Our instrument has some peculiarities worth noting:

- In standard tuning, we can play up to six notes together (since the guitar has six strings, of course).

- We can play the same note on different strings and in different octaves, so in a three-note chord like our C major, we can double one or more notes. It’s still a major chord, but the "color" of the sound changes (easier to hear than to explain).

- We can change the order (in terms of higher and lower pitches) of the chord notes, creating what we call "inversions." Usually, we want the root of the chord as the lowest pitch, but depending on the musical context, the feeling, and our personal taste, we can create different fingerings, each with its own characteristic sound.

- Finally, of course, the number of possible chord fingerings is limited by the stretching capabilities of the left hand.

With these factors in mind, let’s find the C, E, and G notes on the fretboard:

Every combination of strings that contains at least one C, one E, and one G is technically a C major chord.

Every combination of strings that contains at least one C, one E, and one G is technically a C major chord.

Some patterns sound good, others don’t, but in music, there’s no such thing as absolutely right or wrong.

Experiment as much as possible and get a feel for all the options.

Let’s Dissect the Well-Known C Major Chord

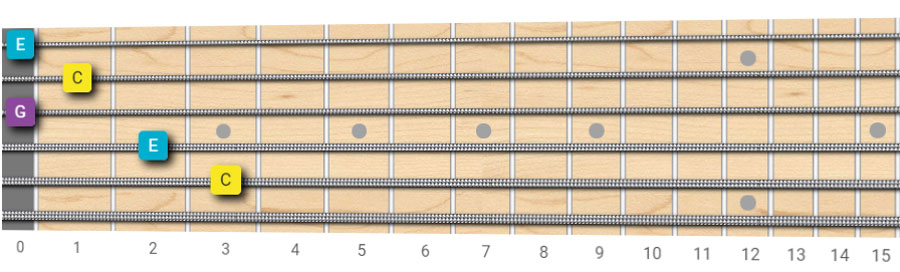

To better understand chord building, let’s start with a well-known shape: the C major chord in the first position.

In the picture below, we’ve highlighted only the C, E, and G notes that make up this shape:

As you can see, this shape includes all the required notes for a C major chord, with C played on two strings and E on three strings.

We can play the lowest E string, but we can also mute it to have the C on the A string as the lowest pitch in the chord.

As always, experiment with these variations and let your ear decide what you like the most.

Other Fingerings for the C Major Chord

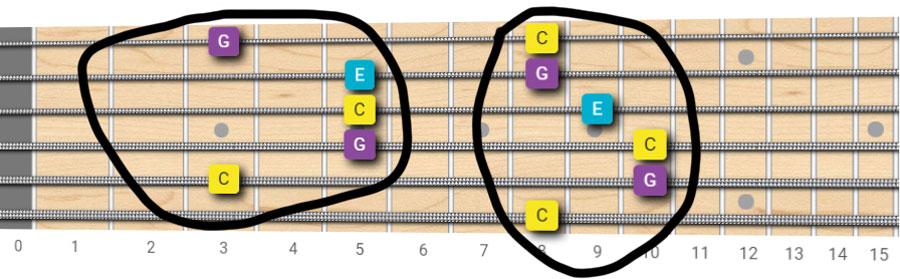

Now we can try to create new fingerings for our C major chord.

As we know, we only need to find some string configurations that contain at least one C, one E, and one G. Let’s look at the image below.

What about the two shapes below?

See? All of the chord shapes above contain exactly the same notes: C, E, and G.

We can use different frets and string combinations—that’s the beauty and challenge of the guitar: having too many options can be confusing at first.

You probably already know the bar chord shape at the 8th fret; it’s identical to the F major chord, just moved up 8 frets.

Do you see the logic in this?

The chord type is always "major," and indeed the shape of the bar chord for F major and C major is the same—what changes is the root. C instead of F, and so the shape is moved to the C root.

Drill down: To learn how to assemble chord tones across the fretboard, check out my chord tones fretboard map resource.

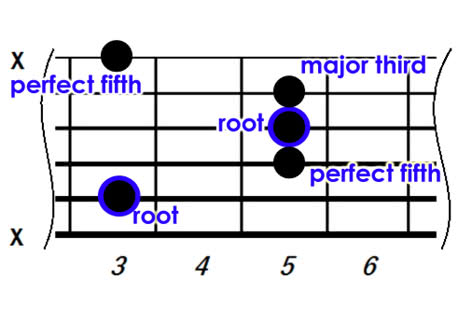

Seeing the Intervals on the Fretboard

Now we can go a step further in our music theory journey and start thinking in terms of intervals.

What does this mean?

Well, the guitar is an instrument strongly based on geometry.

Each interval has its specific shape, so we can assemble these geometries to create chords, without overthinking note names.

Let’s see an example.

We’ve just seen that the C major chord is composed of the root, the major third, and the perfect fifth.

What about the A major chord?

The A major chord is also composed of the root, the major third, and the perfect fifth.

It has the same structure as the C major chord! The only difference is the root—in the case of C major, the root is C, while in the A major chord, the root is A (surprise!).

This leads us to our first chord rule:

All major chords are composed of the root, a major third, and a perfect fifth.

What About Minor Chords?

All minor chords are composed of the root, a minor third, and a perfect fifth.

To create a chord, whether major or minor, starting from any note on the fretboard, we choose the root and then select a major/minor third and a perfect fifth.

That’s all there is to it.

If you want to go beyond major and minor chords and explore the structure of seventh, ninth, diminished chords, and more, check out our complete reference page on chord formulas.

Also, the order of the notes, from the lowest to the highest, matters. This concept is called inversions.

How to Find Intervals on the Fretboard?

Our mission now is to memorize the shapes of:

- Major third interval

- Minor third interval (which is actually a major third, 1 fret lower)

- Perfect fifth interval

Once you have these intervals under your belt, you can assemble them as you like and create any chord you want.

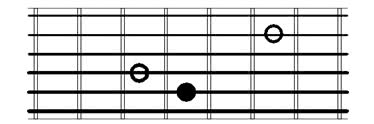

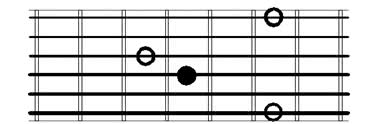

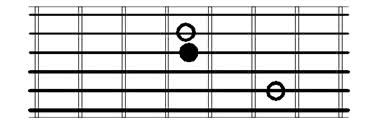

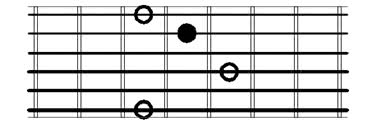

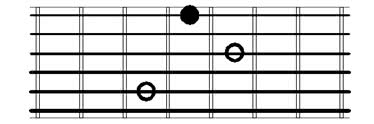

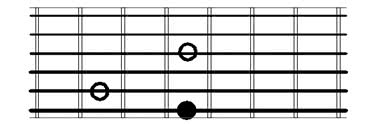

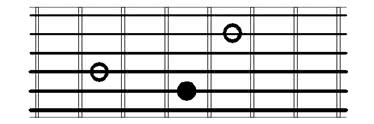

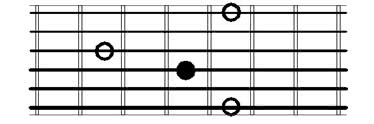

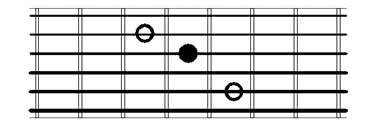

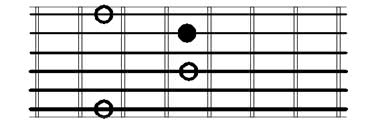

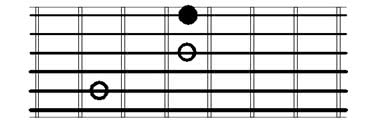

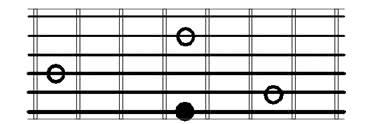

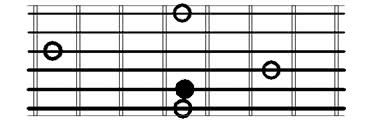

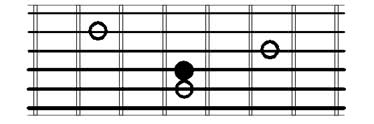

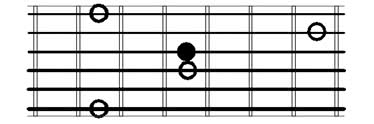

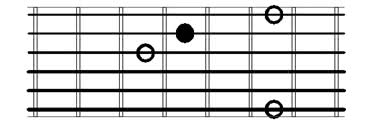

Major Third Intervals

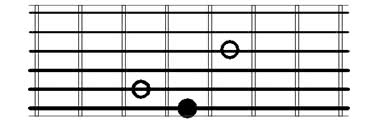

Below, you’ll find the shape of a major third interval starting from each string.

You’ll notice that they all share the same shape, except for the interval between the second and third strings, which is shifted up by one fret.

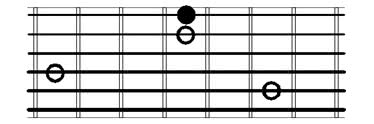

In the following diagrams, the root note is marked with a black dot, while other notes are represented by an empty circle.

Root on the 6th string

Root on the 5th string

Root on the 4th string

Root on the 3rd string

Root on the 2nd string

Root on the 1st string

Minor Third Intervals

The minor third interval is similar to the major third, just one fret lower.

So, if you already know the major third, it’s easy to memorize it.

Root on the 6th string

Root on the 5th string

Root on the 4th string

Root on the 3rd string

Root on the 2nd string

Root on the 1st string

Perfect Fifth Intervals

Root on the 6th string

Root on the 5th string

Root on the 4th string

Root on the 3rd string

Root on the 2nd string

Root on the 1st string

Drill down: In my fretboard intervals map, you’ll find diagrams for all interval types.

Chord Construction - Conclusion and More Resources

I hope that now you have a good understanding of how chords are built and can apply these concepts to the fretboard.

Below are links to several resources that will help you improve your music theory knowledge as applied to the guitar.

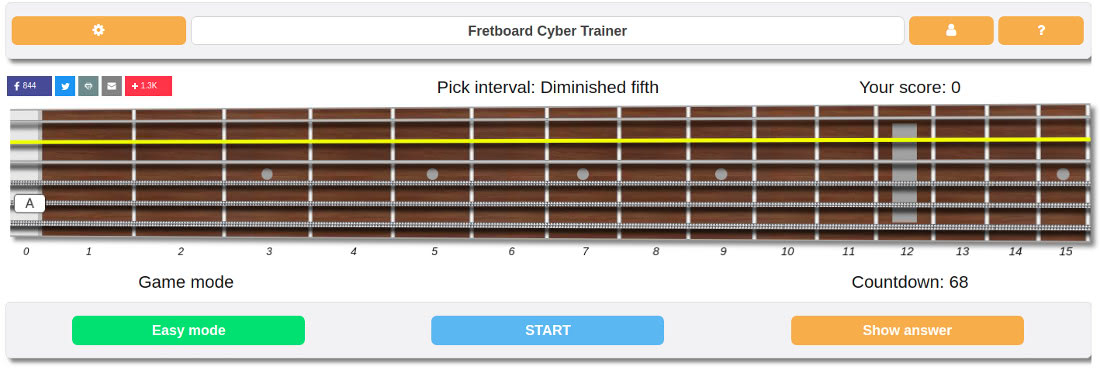

Interactive Fretboard Interval Trainer Game

To help you memorize guitar intervals quickly and enjoyably, we’ve developed an interactive game that’s very effective for internalizing the

fretboard’s geometry.

To help you memorize guitar intervals quickly and enjoyably, we’ve developed an interactive game that’s very effective for internalizing the

fretboard’s geometry.

Give it a try—the game is totally free and runs online in your browser.

Launch the guitar interval trainer now.

Guitar Chords Theory PDF To Download

We’ve created a free PDF ebook that expands on the concepts explained in this tutorial.

It contains fretboard shapes for all possible intervals and shows you how to create chords of different types, such as sevenths, augmented, diminished, and many more.

You can download the ebook, along with many others, in the free download area.

Get your free access to the download area here.

For questions, feedback, and comments, please drop a line below—I’d love to hear your thoughts. Don’t forget to subscribe for free!

FAQ

Why should I learn chord theory instead of just memorizing chord shapes?

Memorizing chord shapes is a good start, but understanding chord theory allows you to intentionally modify chords, add or substitute notes, and even create chords on the fly anywhere on the fretboard. This expands your expressive options and gives you a deeper understanding of the sounds you create.

What is the 'root' of a chord and how does it relate to its name?

The root is the foundational note from which a chord is built and gives the chord its name (e.g., C is the root of a C major chord). All other notes in the chord are defined by their interval distance from this root. When the root is the lowest note played in a chord, it's considered to be in 'root position'.

Why do some notes or intervals have different names, even if they sound the same on the guitar?

This phenomenon is known as enharmonic equivalence. Notes or intervals can have different names (like G# and Ab, or B and Cb) depending on their musical context. Although they produce the same pitch, their specific naming helps clarify their function and relationship within a particular musical key or harmony.

What is the key difference in interval structure between a major chord and a minor chord?

Both major and minor chords are composed of a root, a third, and a perfect fifth. The distinguishing factor is the quality of the third: a major chord uses a major third (four semitones from the root), while a minor chord uses a minor third (three semitones from the root). The perfect fifth remains constant in both.

How can I use intervals to construct new chord shapes anywhere on the fretboard?

Once you know the fretboard patterns for essential intervals like the major third, minor third, and perfect fifth, you can combine these 'geometries' to build any chord. For example, to construct a major chord from any root, you simply find that root on the fretboard, and then apply the fretboard shapes for a major third and a perfect fifth relative to it.

Why do the shapes for intervals sometimes change between the 2nd and 3rd strings on the guitar?

This is due to the guitar's standard tuning. While most adjacent strings are tuned a perfect fourth apart, the G (3rd) string and B (2nd) string are tuned a major third apart. This creates a unique interval relationship between these two specific strings, causing any interval shapes that span across them to be adjusted by one fret compared to patterns on other string pairs.