Understanding Chord Inversions

How To Use Octaves to Create Inversions Up and Down The Fretboard

In this tutorial, I'll show you a smart way to use octave intervals for generating chord inversions.

We'll do this process with the help of the fretboard, so our neck navigation skills will improve as well.

Fretboard Octave Interactive Tool

Use the interactive tool below to play with the fretboard diagrams for this tutorial.

What Are Chord Inversions?

If you already studied a bit of chord construction theory, you already know that a chord is formed by three or more notes stacked one on top of another.

Usually, we put the note with the lowest pitch at the bottom; this is the so-called root of the chord and gives the name the chord itself.

For instance, if we have a C at the bottom, the chord is named C "something" chord.

The remaining notes are at different distances from the root.

These distances are called "intervals"

For example, in a major chord, we have the root, a major third, and a perfect fifth.

A major third is 4 half-steps from the root, while a perfect fifth is 7 half-steps.

Back to our C example.

If we stack a major third and a perfect fifth on our C root, we get a C major chord.

The "something" named above is now "major", because we have root, major third, and the perfect fifth.

Each intervals combination has its unique name, check our complete chord formula table here.

Generating Chord Inversions

Depending on which note of the chord is at the lowest position, we can have different configurations:

- Root Position: when we have the root as the lowest note, we say that the chord is in the root position.

- First Inversion: if we move the root up to the upper octave, we have the third as the lowest note. This is called first inversion.

- Second Inversion: again, we move the third to the upper octave, and now we have the fifth in the lowest position. This is called second inversion.

We can easily visualize this process on the fretboard, with a double benefit: understanding the logic behind those triads shapes, and improving fretboard navigation confidence.

I've learned this trick by Ted Greene, the legendary jazz guitar master.

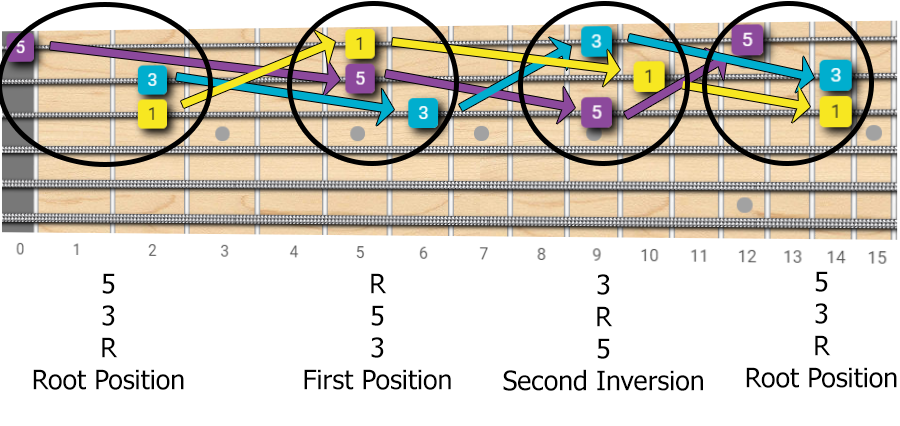

We start with a triad in root position, and we move one note at a time to the upper or lower octave, trying to keep the shape fingering closed (on adjacent strings) and easy to play. Have a look at the images below:

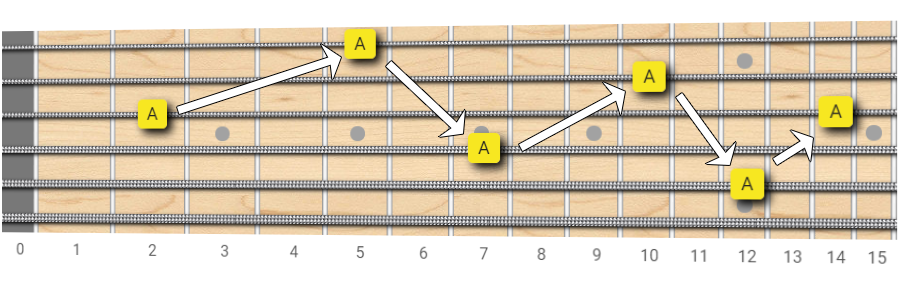

In this first picture, we can see where to find the same note moving horizontally by octave intervals.

Take some time to play these paths and get familiar with them.

Now we can take a triad shape, and apply this octave trick to all its notes, one at a time.

From the root position, by moving one note at a time, we get the first inversion, then the second, then we go back to the root position.

Again, play these examples on your guitar and listen to the different nuances between the inversions.

Of course, this method works for each type of triads: major, minor, augmented and diminished, and for all the strings.

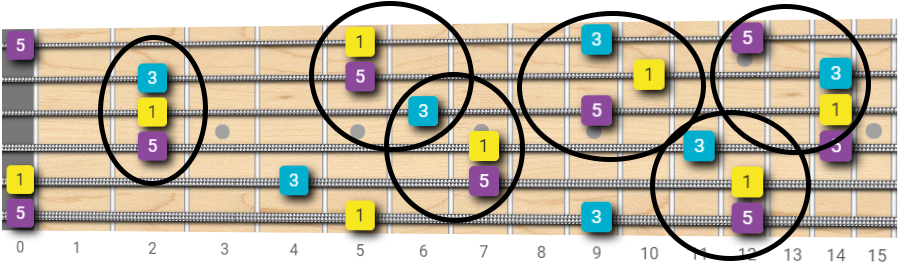

Have a look at the diagram below (this time I did not draw the octave arrows to keep the diagrams clearer).

I've highlighted some of the main triad shapes that one can find over the entire fretboard.

See how the root (R), the third (3) and the fifth (5) are interconnected by octave intervals.

Now it's your turn: use the diagrams below to create your own 3 notes triad-shapes, using octave intervals to move across the fretboard, for the other triad types: minor, diminished, augmented

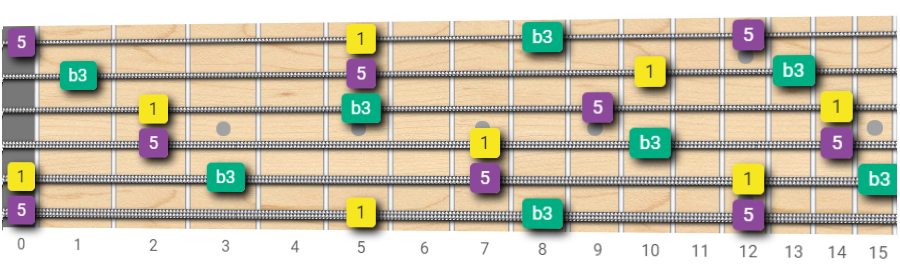

Minor Triads Fretboard Map

A minor triad is composed of the root (R), minor third (b3) and perfect fifth (5).

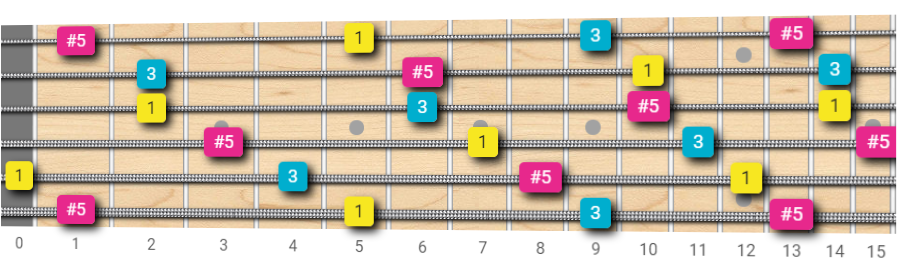

Augmented Triads Fretboard Map

An augmented triad is composed of the root (R), major third (3) and augmented fifth (#5).

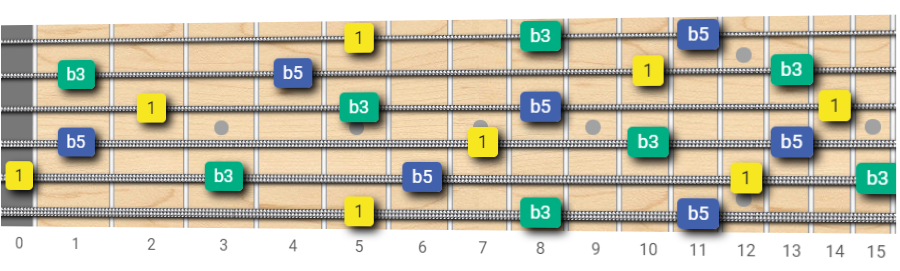

Diminished Triads Fretboard Map

A diminished triad is composed of the root (R), minor third (b3) and diminished fifth (b5).

Four Tones Chords

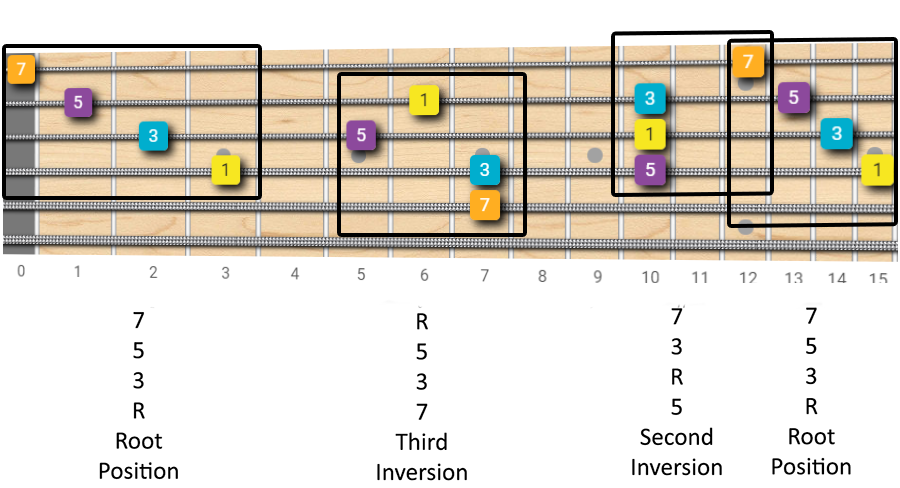

Now what happens when we deal with four notes chords, such as dominant chord or other types of chord?

The process is the same, but as we have an additional note (usually a 7th interval, major, minor or diminished), and so 4 notes per chord, we can have a third inversion, in which the 7th is at the lowest position.

The diagram below shows you this concept applied to the F major 7th chord.

With 4 notes the combinations and thus the complexity explodes, as we have many different options for staking those 4 notes.

But the logic still remains the same.

How Do You Call Fifth Third Root Inversion?

Recently, a FaChords visitor asked a smart question:

Question:

If Fifth Root Third (5 R 3) is a 2nd inversion, what is a Fifth Third Root (5 3 R)??

It's theoretically still a 2nd inversion because of the low 5, but is it??

Answer:

The name of the inversion is decided by the note that is at the bottom, it does not matter the order of the other notes, so 5 R 3 and 5 3 R are called 2nd inversion both.

Chord Inversion: Conclusions and Further References

Unlike the piano keyboard, the guitar fretboard is more complex to understand, as we can play the same note in different places.

Octave intervals are a way to manage this complexity. In my complete ebook "Chords Domination | Play Any Chord You Want Across All The Fretboard ", I go deep in intervals and chord construction, with the help of several full fretboard maps for more than 40 different chord types. Check it out here.

To stay updated on new tutorials, and get access to the free download area, subscribe here.

FAQ

What is the primary benefit of learning chord inversions using octave intervals on the guitar?

Learning chord inversions through octave intervals helps guitarists understand how different voicings of a chord are related across the fretboard. It improves fretboard navigation by highlighting where chord tones repeat in higher or lower octaves, making it easier to discover new chord shapes and connect them seamlessly.

How do I identify which inversion a chord is in on the guitar?

The inversion of a chord is determined by the lowest-pitched note being played. If the root is the lowest note, it's in root position. If the 3rd is the lowest note, it's a first inversion. If the 5th is the lowest note, it's a second inversion. For four-note chords, if the 7th is the lowest note, it's a third inversion.

Does the order of the notes above the lowest tone affect the name of a chord's inversion?

No, the specific order of the notes above the lowest-pitched tone does not change the inversion's name. Only the lowest note played determines whether the chord is in root position, first inversion, second inversion, or third inversion.

Can the octave interval method for creating inversions be used for all types of chords?

Yes, this method is versatile. It works for all types of triads (major, minor, augmented, and diminished) and can also be applied to four-note chords, such as major 7th or dominant 7th chords, which introduce the possibility of a third inversion.

Why is it recommended to move one note at a time by octave intervals when practicing inversions?

Moving one note at a time by octave intervals helps you systematically explore and understand how chord voicings are constructed. This approach, advocated by guitar masters like Ted Greene, allows you to observe the subtle changes in chord quality and practice keeping the new shapes easy to play on adjacent strings, enhancing both your theoretical understanding and fretboard dexterity.

What is the difference between a root position chord and its inversions?

A root position chord has its foundational note (the root) as the lowest-pitched note. Inversions are alternative voicings of the same chord where a different chord tone (like the 3rd, 5th, or 7th) is placed as the lowest-pitched note, creating a distinct sonic quality while maintaining the chord's identity.

How can I achieve a 'third inversion' when most chords only have root, first, and second inversions?

A third inversion is only possible with chords that contain at least four distinct notes, typically 7th chords (e.g., Cmaj7, G7). In this case, the 7th of the chord becomes the lowest-pitched note, creating the third inversion. Triads, by definition, only have three distinct notes and thus only have a root position, first, and second inversion.