Blues Guitar Riff

12 Bar Blues In The Style Of Lynyrd Skynyrd

In this lesson, I want to show you a Blues riff that reminds the sound of Lynyrd Skynyrd.

I'm going through the creative process and the music theory hooks that helped me conceive this sequence, to help you learn how to create your own riffs.

Feel free to make a full song out of these notes, it would be even cool to have someone singing over it!

Melodic And Harmonic Analysis

Before going forward, be sure to have a look at the video, using also the tabs on screen to understand better what's going on.

Please like and share the video as it will be really helpful for this site, thanks!

In the following, I'm going to break down the riff bar by bar.

Riff Structure

The structure of the riff is the classic 12 bar blues. So we have:

| 1) A (I) | 2) A (I) | 3) A (I) | 4) A (I) |

| 5) D (IV) | 6) D (IV) | 7) A (I) | 8) A (I) |

| 9) E (V) | 10) D (IV) | 11) A (I) | 12) E (V) |

Time Signature

The riff is in 4/4, at 90 bpm speed.

However, as we're going to see, it has a couple of rhythmic syncopation that will challenge you a bit. Keep reading :-)

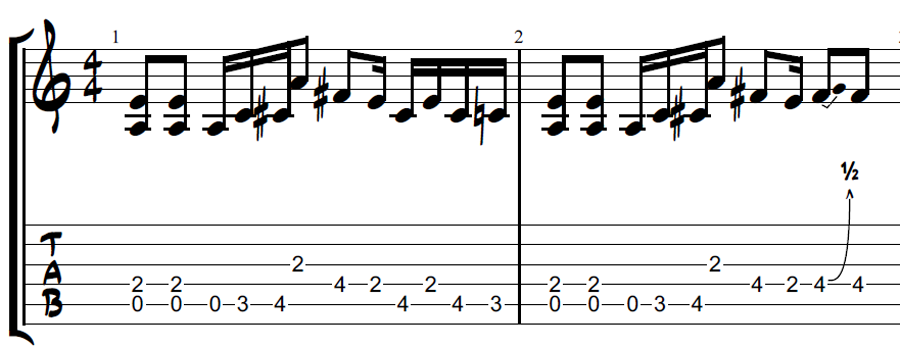

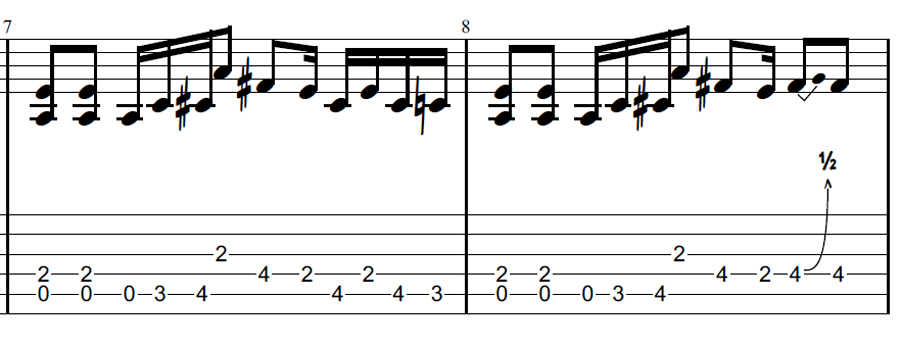

Bar 1-4

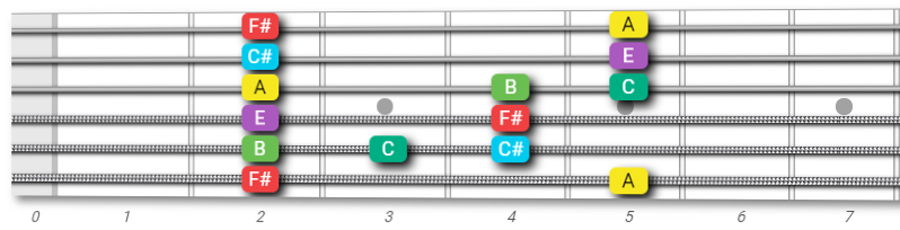

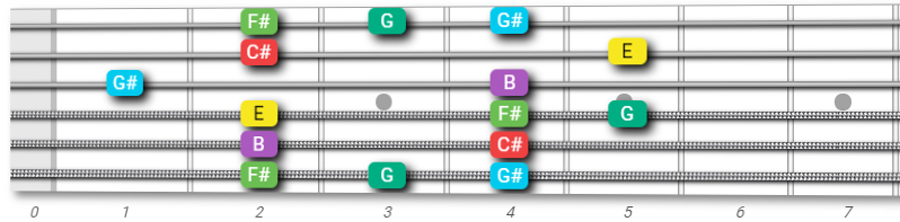

As the riff is in the key of A, and we are in the realms of the Blues, the ideal candidate for the first four bars (A) is the A Major Blues Pentatonic Scale, which is A B C C# E and F#.

A Major Blues Pentatonic Scale

The riff starts with an A power chord and goes up and down along the A major blues pentatonic scale.

This happens in bars 1 and 3.

In bars 2 and 4, there's a half-tone bending (F# to G) that sounds sooooo blues. Why?

G is the b7 of A7 chord, and it's the note that gives the dominant feeling.

The same flavor of the Mixolydian mode.

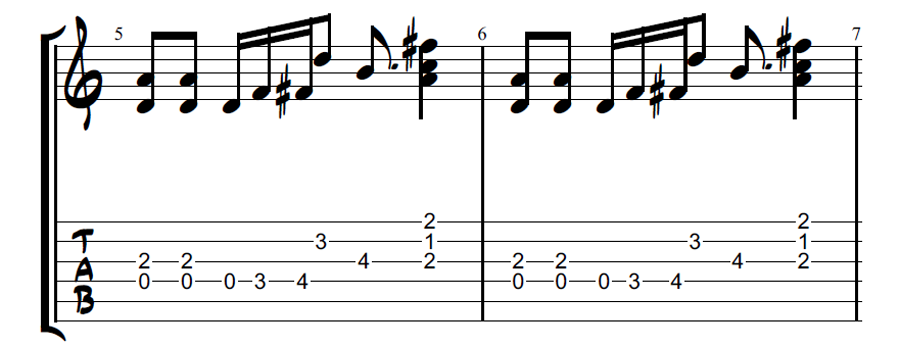

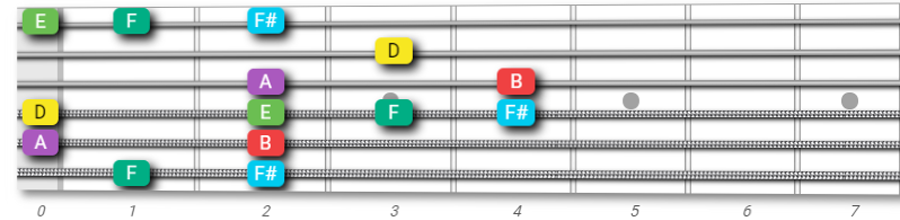

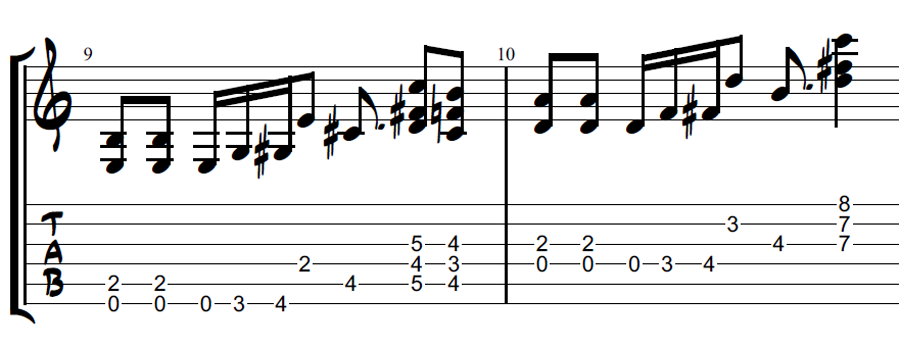

Bar 5-6

At bar 5 and 6, the Blues structure brings us to D, so the reference scale now is the D Major Blues Pentatonic Scale.

We go up through the scale exactly as we did before, this time starting from the D power chord, but we don't come back, instead, we play a D7 on the fourth beat.

Notice the dotted B right before the D7 chord (4th fret on the G string).

In music theory, the dot beside a note increases the duration of that note by half, so that B lasts one eight note plus a sixteen note, the time needed to make the D7 chord fall on the the fourth beat of the bar.

At first the timing is a bit tricky, so take your time to practice this passage.

Bar 7-8

Bars 7 and 8 are exactly the same as bars 1 2 3 and 4, because we are playing the Blues!

(be sure to get that half-step bending right)

Bar 9-10

At bar 9, following the Blues structure of the riff we land on the V degree of the key, which is E, so the scale to follow is now the E major blues pentatonic scale.

On the last beat, we play a couple of shell chords, D7 and C#7, that give great dynamics.

Bar 10 switches again to the IV degree, D, this time we play the D7 on the 7th fret (x-x-x-7-7-8), this again is a shell chord composed of the root (D), major third (F#) and minor seventh (C).

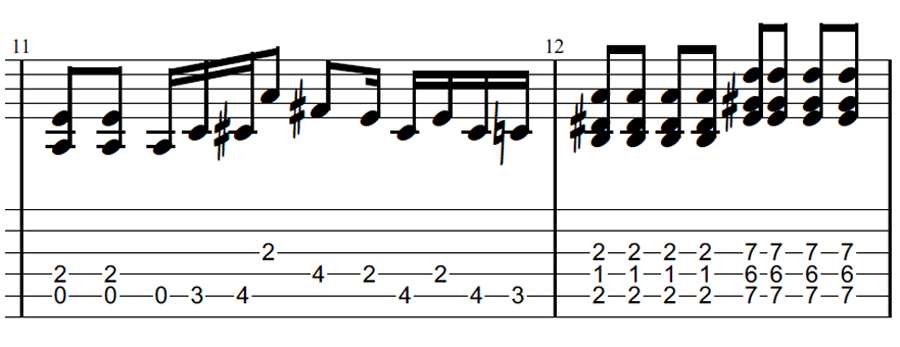

Bar 11-12

Bar 11 is still in A so we do the same as bar 1, while at bar 12 we have an interesting turnaround:

B7 and E7 shell chords in eight notes that communicate a sense of conclusion and desire to start again.

Notice the V to I cadence (E7 to A7) which is so common and familiar.

Conclusions And Free Resources To Download

As we have just seen, a mixture of pentatonic scales, small dominant chord fragments, and rhythmic variations can still create something interesting, even if in a mature genre like the Blues.

In particular, shifting the same pentatonic scale across the 1, 4 and 5 degrees of the progression, can create nice effects.

I hope this tutorial has given you some insights to create your own music.

It's good to learn scales, chords, and covers, but, in my opinion, the best feeling in the world is to create something and share it with others.

Here are the free download related to this lesson:

That's all for today, to stay updated subscribe here.

FAQ

Why is the A Major Blues Pentatonic scale used for the initial bars of this blues riff?

For a blues riff in the key of A, the A Major Blues Pentatonic scale (A B C C# E F#) is presented as an ideal choice for the I chord. This scale provides the characteristic blues sound that fits the 'Lynyrd Skynyrd' style being taught, forming the melodic foundation for the initial four bars.

What is the purpose of the half-tone bend (F# to G) in bars 2 and 4 of the riff?

The half-tone bend from F# to G introduces the G note, which is the flattened seventh (b7) of an A7 chord. This specific note is crucial for creating a 'dominant feeling' that is characteristic of the blues. It brings a tension similar to the sound of the Mixolydian mode, enhancing the bluesy flavor of the riff.

How does the riff adapt to the chord changes in the 12-bar blues progression?

As the 12-bar blues progression moves through its I-IV-V chord changes (A, D, E), the riff strategically shifts its reference scale. For the D chord (IV degree), the D Major Blues Pentatonic is used, and for the E chord (V degree), the E Major Blues Pentatonic is applied. This approach ensures the melodic lines remain harmonious and bluesy over the changing chords.

What is a dotted note and how does it affect the rhythm in this riff?

A dotted note increases its original duration by half, introducing rhythmic syncopation. In this riff, a dotted B in bar 5 makes the timing a bit tricky. It's used to precisely place the D7 chord on the fourth beat of the bar, adding a specific rhythmic nuance and challenge to the timing.

What is the function of shell chords in this blues riff?

Shell chords are used in the riff to add dynamics and outline the harmony efficiently. For instance, in bars 9-10, D7 and C#7 shell chords are played for dynamic effect. In bar 10, a D7 shell chord (root, major third, minor seventh) is used to clearly define the D7 sound with fewer notes, and B7 and E7 shell chords in bar 12 create an interesting turnaround effect.

What does the V to I cadence at the end of the riff achieve?

The V to I cadence, specifically the E7 to A7 progression in bar 12, serves as a common and familiar blues turnaround. It provides a strong sense of conclusion to the 12-bar progression. Simultaneously, it builds anticipation and creates a natural desire for the riff to repeat, effectively signaling the end of one cycle and the start of another.